MSc in Evolutionary and Adaptive Systems at the University of Sussex: A Year in Review

As you may know I have spent the last year studying at the University of Sussex. I thought it was time for a blog post about my experience there. I will keep this post mostly confined to my life on and around campus, omitting most personal matters and complications before and along this very intense year. I would like to thank my family for enabling me to study there; special gratitude goes to my mother for her love and constant support throughout. Many thanks also to my lovely house mates, as well as my old and new friends for keeping me sane.

I first heard about the MSc programme Evolutionary and Adaptive Systems (ironically abbreviated the "EASy MSc") at the University of Sussex in 2009 at the European Conference for Artificial Life (ECAL), where I had been introduced to its (then) course convenor Inman Harvey. Speaking of ECAL'09, apparently nobody has received their proceedings. Chairman George Kampis did not care to reply to my latest inquiry at all. Very disappointing. Anyway, I had a keen interest in the topic of Artificial Life. Writing algorithms that work like nature does? Simulating living systems? Yes, please! When I found out that the course came also with some cognitive science and neuroscience, I was sold completely. I finished my BSc in computer science at the University of Klagenfurt and moved to England. At this point let me thank Andrew Pegge for his generous donation to the University that made possible a reduction of the tuition fee for students of my programme. I was one of the two lucky people to receive it that year.

My studies came in the format of a one-year MSc rather than two and in three terms of three months each rather than the two semester years I was used to from Austria. Autumn term lasted October to December, spring Term January to March and summer term roughly May and June. In practice, however, the work from autumn term lasted to spring term, the work from spring term lasted to summer term and during summer term I did my dissertation which took all the way to September. My weeks had seven workdays. Did I mention it was an intense year? The best part was when I handed some of my work in late due to sickness and received a late-penalty for one of them. The reasoning: Students are supposed to plan ahead and leave some room in case they get sick. I couldn't help but laugh.

So here is what the programme consisted of (optional classes were subject to change). Since this is a pretty long read, I've also inserted jump marks for your convenience.

-

Autumn Term (core)

- Academic Development (core)

- Intelligence in Animals and Machines (core)

- Artificial Life (core)

- Mathematical Methods for Complex Systems (core)

- Object Oriented Programming (core, but could be swapped for "Machine Learning" if already proficient in OOP)

-

Spring Term

- Adaptive Systems (core)

- Neural Networks (core, but could be swapped for "Generative Creativity" if already proficient in NNs)

- Neuroscience of Consciousness (option)

- Sensory and Motor Functions of the Nervous System (option)

- Summer Term / Dissertation

And here are two more jump marks for the remaining sections of this post:

The other options offered that where offered: "Generative Creativity", "Sensory Systems and Receptors" and "Computational Neuroscience". Regarding these options, I thought I would not need a university to learn about Generative Creativity, and Sensory Systems and Receptors was too low-level for me to appreciate. I was interested in Computational Neuroscience, but I learned that it required a lot of hard math that I could not possibly catch up with in the little time I had. Also, it was taught by the same professor as both core classes that term. I did not know him yet and what if I did not get along with him? In retrospective, I made the right choice. I would have taken Generative Creativity over Sensory and Motor Functions of the Nervous System to have some more fun in the second term, though.

The following are my comments on all of the classes. I have uploaded a selection of essays and reports that I still like, you can find them linked from the text. If you are interested in anything in particular that I did not upload or have any questions/comments, feel free to contact me.

Autumn Term

Academic Development

"Plagiarism is bad, mh kay? Don't plagiarize, mh kay?" This class lasted only for three weeks for most of us, a few hours per week. The goal was for us to learn how to know plagiarism when we see it and how to avoid plagiarizing. I did not dislike the class, but that was only because of the absolutely stunning woman who taught it. Maybe I should have asked her out.. ah well.. About three weeks into the term there was a test, I passed it and did not have to take this class anymore.

Intelligence in Animals and Machines

A great class. One of its goals was to introduce us to a new view of what we mean when we say "intelligence". We have been shown how animals behave "intelligently" as individuals or collectively and have been brought to an understanding from which intelligence can be understood in terms of behavior. The classical view of intelligence as reasoning or planning has been broadened to include any behavior appropriate to the circumstances. Once these circumstances stop being the way they used to, e.g. by means of human interference mediated by a nasty scientist, the behavior that we thought to be intelligent often breaks down completely, displaying how rigidly preprogrammed this seemingly intelligent behavior really is. An example is the digger wasp which places its caught prey in front of the entrance of its little cave. It then checks whether the cave is is occupied by somebody else. If everything is alright, it comes back out and drags the meal inside. Perfectly intelligent behavior? If you move the food an inch or so while the wasp is in its cave, the insect will come back out, grab the food, drag it before the cave and check again. Basically, since the food is gone when it emerges from the cave, it resets to "find food"-mode, it finds food an inch away and drags it to the entrance, entering "check cave"-mode again and again and again. It became very clear that intelligence is something human observers attribute to other beings because of how they (the human observers) themselves are: Birds don't fly by planning how to move their wings, they just do it because of the way they are as a whole - brain, body and environment.

We also learned to take that new view of intelligence as behaving appropriately in a given environment and view it from a technological point of view. Instead of building robots that can play chess, we learned about building very, very simple robots called Braitenberg Vehicles, that could e.g. follow a light source. The theme was really "How simple can you make this thing before it stops doing something interesting?".

I have one negative point about this class: we never went past the stage of very, very simple robots and neither did the researchers. Following light or sound, and avoiding obstacles, and that was it for the most part. There is some research (e.g. the ECCEROBOT) attempting to demonstrate that human cognition needs a human body, which is a pretty cool idea, but, generally speaking, the best this "New AI" can do at the moment is manage to clean your carpet automatically and avoid the obstacles that inhabit a typical living room.

The format of the class was two one-hour lectures each week, plus a one-hour seminar for which we read papers beforehand and then discussed their content. The assessment consisted of an essay for which we could pick a topic rather freely. I wrote about theoretical software agents, which, using a very simple model of human consciousness would be embedded in human-computer interaction in a way that would allow them to display aspects of human cognition. This essay eventually led to the topic of my MSc thesis.

Artificial Life

Starting from the question "How do we find out whether something is alive", we explored the evolutions of cellular automata, of artificial chemistries, even of whole programs and parameters for robot controllers based on artificial neural networks, we learned about how evolution solves problems and how to exploit evolution to make it solve our own problems. Being in line with the discussion on intelligence, the problem-solving aspect belongs entirely to the human observer. Evolution is a "blind watchmaker" (as Richard Dawkins called it) rather than an engineer. We learned not only how nature can find solutions to "simple" NP-hard problems, but also "design" morphologies (e.g. bodies of animats) in computer simulations. Looking at these simulations made the process of evolution and its limitations absolutely clear. For example, there is no such thing as evolutionary "optimization". Evolution is inherently lazy. If it can get away with doing "good enough", it will do so. Your chances of finding the best solution to any problem are close to none as long as you give evolution the chance to get away with mediocrity. Often, evolutionary processes will drift ("Genetic Drift") aimlessly for a while and then suddenly lead to explosive growth of complexity as described by the theories of neutral networks (mind the 't') and punctuated equilibria. In Darwinian evolution, the Cambrian explosion is assumed to be such an event.

We learned about the special process called Autopoiesis (see the book "The Tree of Knowledge" by Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela), which serves as a fundamentally new (well, more like 50 year old) way of describing what makes a living system living. This class took the magic out of life (in a good way). Before I started this MSc, I already viewed life as a special kind of pattern. This class brought it all together and from the first replicators to myself, there is a clear lineage that I came to understand. This lineage is generated by the inevitability of complex dynamic interaction of replicating autopoietic systems and their environments. See also my blog post on the "tree of life".

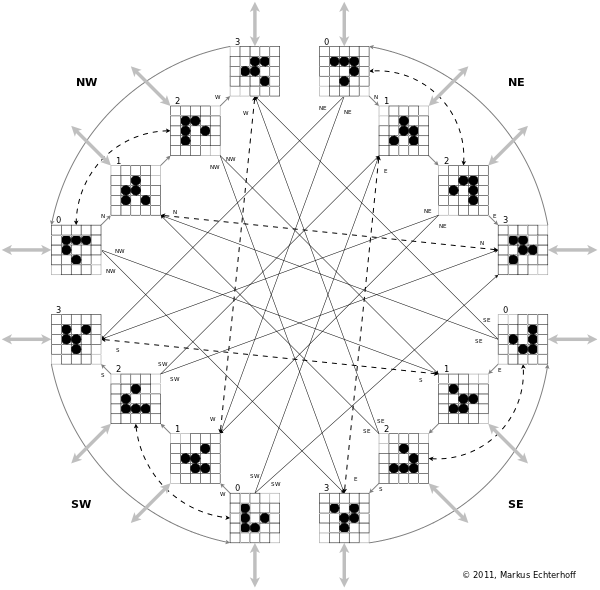

The class came in the same format as Intelligence in Animals and Machines. For assessment we had to do a programming project and write a report on it. I analyzed, in a rather phenomenological way, a glider in Conway's Game of Life with respect to autopoietic organization. I was expanding on previous work by Randall Beer (his paper is titled "Autopoiesis and Cognition in the Game of Life"). You can find my report here. Also, I did this diagram of the cognitive domain of a glider. See my report for details, I just put the diagram here because I think it looks awesome.

Mathematical Methods for Complex Systems

Yeah, math. Hard, brutal, unforgiving math. But it was a pretty awesome class. We had about two weeks to get to terms with (or rather refresh our knowledge of) functions, notations, matrices and vectors. We then went on to differential calculus, numerical integration, dynamical systems analysis and did some probability and statistics. All along we had exercises in Matlab, simulating neurons (without having any idea what they do for now, just the mathematical analysis), analyzing search algorithms and how they perform on particular fitness landscapes, and some magic involving Eigenvectors. I did not understand all of the math involved, but at the end I knew I didn't have to. All I had to understand was how to feed Matlab an iterative process, have it simulate it and then analyze the results. Turns out there is a different way of mathematical understanding. Instead of analyzing formulae and attempting to understand them at the level of the axioms that make them possible, you can also run them and see what they do. I still don't know what the hell an Eigenvector "is", I know the formula which does not make much sense to me, but I can hack it into Matlab now, see how it correlates to behavior of some system, and get an understanding of what kind of information it could usefully describe. I wish all math classes were like this.

The class consisted of a weekly lecture and lab class in which we did Matlab exercises as mentioned before. The assessment was based on the grades of all of the exercises and a final project of our own choosing. I explored the history of classification of cellular automata, mainly based on measures of complexity. It was a lot of fun. I have uploaded the report for the final project in case you are interested.

Object Oriented Programming

I can't say a lot about this class. After the first lecture, held by a tough but sympathetic Russian lady, I just did the exercises. Basically, this was your run-off-the-mill beginner's guide to programming in Java, which I was quite comfortable with already. Our convenor said we could substitute this class for another, but on the other hand we could also take the easy mark. I thought about it and considering the substitute was Machine Learning, I went for the easy mark. I did not regret my choice because I spent most of my days studying for that math class.

Spring Term

With spring term came the departure of the professor who held the majority of classes of autumn term. I quite liked his style and I quite disliked the style of the professor who held the majority of classes in spring term. Clearly, as a student, I am used to levels of satisfaction rising and falling with the pedagogical finesse of the teacher, but for ten times the tuition fees (compared to my undergrad studies) I somehow expected ten times the quality. So while I still learned a lot, I can't help but feel I could have learned more if the knowledge had been presented in a more accessible way.

Adaptive Systems

A great class. What is adaptivity? What is adapting, what is adapted and what is the difference? Last year it was held by the other professor and I wished he could have stayed around to teach it again. This class just seemed more suited for him. But let's talk about the actual contents of the class. It picked up where the previous classes left off. There was more evolution, more autopoiesis, more dynamical systems, some neural network robot control, homeostasis, ultrastability (see the paper "Design for a Brain" by William Ashby) and, generally speaking, all kinds of autonomous, adaptive control mechanisms that didn't have to be designed in detail but kind of worked by a dynamical system interacting with an environment in a way that both were being preserved. For example, evolving Continuous Time Recurrent Neural Network (CTRNN) controllers using artificial evolution to have robots avoid obstacles. Robots that jump like babies were also quite entertaining to watch. A most interesting phenomenon was explained during a break. As is common knowledge, women living together tend to synchronize their periods. As is not common knowledge, however, they do so, we have been told, via chemicals transpiring from their arm pits. It's pretty random, I know, but it demonstrates perfectly how complex dynamic systems just loooove to synchronize, to reach some shared equilibrium state and then stay there until perturbed.

Again we had lectures and discussions about papers we read. The assessment was, again, a programming project and corresponding report. I could not come up with anything really interesting that I could get done in time. Of course I thought about training artificial neural networks to do something, but I could not bear the thought of programming yet another obstacle avoiding piece of software agent. From a list I picked the problem of traffic allocation in communication networks. Instead of a clever routing algorithm, however, I wanted to find out whether I could evolve network topologies that were particularly fit to route specific phone traffic. I programmed a phone call simulator and I evolved topologies, but not with great success. The fitness landscape was too rough for evolution to work noticeably better than random search. I did not have the time to revise my approach, so I had to hand in negative results.

Neural Networks

This class taught us how to build neural networks (duh). We learned about single and multi-layer perceptrons, radial basis function networks and had a look at support vector machines (that confused the hell out of me). In addition to different network models, we learned about various types of learning: supervised, unsupervised and reinforcement learning, about pre- and post-processing of data and committee machines. At the end of the day, neural networks are a method to match some unknown function. The math involved can become terribly complex and if you get an outcome that differs from what you expected, it is kind of difficult to assess whether you have a bug in your code, in your math, in your training data, in your parameters, or if the method you try to employ just generally fails to capture the essential parts of the problem you seek to solve. There are rules of thumb, but mostly you have to rely on experience, and the occasional lucky guess.

Format: lectures and lab class with exercises. Those exercises... I was constantly lagging behind. I really wanted to understand one thing before I moved to the next, but there was math everywhere, math I had to learn before understanding how it applied to neural networks. The math class from the previous term prepared me for some of the issues, however, it was not enough, not by a long shot. The assessment was based on two exercises. One involving a single layer perceptron solving some tasks and another having a multi-layer perceptron as well as a radial basis network solve the same (classic) problem of predicting house prices in Boston. I did it, I understood the principles, I passed the class, but I lost some of my enthusiasm for neural networks in the process.

Neuroscience of Consciousness

This was one of my favorite classes. I knew a little about consciousness from a class I took as part of my Bachelor studies in Austria but my knowledge about neuroscience was that a brain is a grayish mass formed like a walnut and textured like a ripe avocado. Also, it is some kind of neural network with lots of chemical extras like gases and stuff that add additional complexity.

There was so much to learn in this class. How can you make consciousness tangible for scientific study? What is its function? Can it be quantified or simulated? What states of consciousness are there? Which functions can be performed unconsciously, which need conscious attention? What does consciousness have to do with cortical plasticity, with self, with volition, with attention, with interoception? What can go wrong with consciousness and, finally, how did this consciousness come to be, evolutionarily speaking, and to what extend are animals conscious - is it a difference of kind or of degree?

Want answers to these questions? Well, so does everybody else, including the people who held the lectures. There are lots of interesting ideas, theories and experiments, but in the end nobody has a clue. The current trend is to search for a Neural Correlate of Consciousness (NCC), a mapping between objective states of brains and subjective states of experience. Only one problem: each brain is different. Somehow normal, unperturbed human brains perform roughly the same function with roughly the same areas. That much has been exposed using modern neuro-imaging devices, but the exact processing differs. So while we can tell when someone is picturing themselves involved in a motor-sensory intensive task, we probably couldn't find a stable qualifier to tell whether a subject is thinking about playing tennis or playing baseball. Nonetheless, progress in the field has significantly helped e.g. in determining whether unresponsive patients are conscious or not.

Despite the uncertainties, some things became pretty clear. For example, any belief in free will went pretty much down the drain in new recreations of Libet's classical experiment. With action potentials indicating particular actions seconds before the felt urge to act and subsequent onset of action, the question is not whether there is free will, but how to deal with the fact there is no such thing. According to current science, there may be room for a late veto decision, so not all is lost. When your brain is preparing to stick that hand of yours into a fire, there is still time to not do it (see e.g. Patrick Haggards review entitled "Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will"). But is that decision free in the sense of free will? What is this freedom anyway? A kind of randomness? A divine spark? Of course anything related to free will raises all sorts of interesting ethical questions.

I read a lot of fascinating papers for this class. You may have heard about phantom limbs, but have you heard of phantom penises before? They do exist. The only negative comments I can make about this class are that a) the professor failed at replying to my email inquiries and b) I got a crappy pass mark for a paper I thought was really good. It was not wrong or anything, I failed to mention some prior research done by a guy I never knew existed, and the focus of my work was not exactly where the lecturer wanted it to be. Oh well, at least I enjoyed writing it and I learned a lot.

Sensory and Motor Functions of the Nervous System

This was officially the most boring class of the entire programme. Also, the lecturer was unprepared for Master's students being in his class that he claimed was designed for undergraduate students. He was a very kind person, but completely inflexible to the point that it seemed downright neurotic. It was a mess. We had very strict requirements for the essay we had to write. In the beginning he wanted us to prepare an essay on a topic of his choosing. There was a pool of topics consisting of the contents of the weekly lectures and we were to be assigned a topic randomly. Of course we talked to him about that. After some contemplation, he allowed us to choose from these topics. However, we were not allowed to go anywhere from there. I wanted to find out about hardware/software implementations of Neural Darwinism. No go. Neuronal Replicator Hypothesis? No go. He would not know how to grade it, he said. I had the flu at the time and was emailing with him. I made two attempts at compromising and then just accepted that this was going to suck. I ended up with Neural Darwinism in the context of the development of visual cortex, with some cortical plasticity of sensory-motor cortex mixed in. Basically, I had to read papers by nasty researchers dissecting the brains of little kittens, born from cats that were reared in the dark and/or surgically or chemically blinded on one eye, or similarly gruesome experiments performed on other cuddly animals. Somehow some scientists seem to have lost the connection with their compassion for other living beings in the process of doing science.

Summer Term / Dissertation

When the time for picking a dissertation topic arrived, I was kind of satisfied with the knowledge I had gained from the classes and I did not feel the need to go into more detail on most of them. But I had to pick a major programming project and write a 12,000 word dissertation on it. I browsed through the extensive database of project ideas and nothing resonated. I was quite burned out already, so whatever I did it would have to spark the strong desire to just do it. I found something. Remember I wrote that essay for Intelligence in Animals and Machines? Ya well, I wanted to build the then theoretic software agents. I wanted to build a software agent based on the Global Workspace theory of consciousness, I wanted to feed it words during normal human-computer interaction, I wanted these words to compete for space in a memetic evolution and I was hoping that "concepts" would form as ensembles of memes, and be naturally selected, much like neuronal groups in Neural Darwinism. I thought it highly probable that with enough interaction, some traits of human cognition would emerge from this.

I looked at my ideas and reduced the project to a rather simple use case. The software agent would consist of two parts. A browser plugin which a user would utilize to feed the agent input and the actual program that would constantly run in the background. The evolution of memes in the memory of the agent would come about by applying selective pressure based on the emotions the user has when viewing a particular website. The trained agent should be able to browse the WWW autonomously and simulate its user's reactions to the content encountered. During the process, the agent would generate connections between memes and emotions that would guide its behavior. The idea was that, given sufficient training, the browsing behavior of the agent would converge to that of the user and allow the agent to truly autonomously navigate the WWW as if it were the user.

I wrote a proposal and entered it into the project database. Nobody answered my call for a supervisor. "Maybe they didn't access the database at all", I thought, so I started looking for a supervisor myself. And I found one. My supervisor was interested in the project, had some experience with both computers and philosophy of mind, and agreed to supervise me. A perfect start.

There were two major problems with this project, however. a) it was too big a project, b) it took a wrong turn right in the beginning. After I presented my ideas to my supervisor, the point came where he asked me how I would assess whether my project was a success. "Well..", I thought, "I want to build it and analyze it. A success is when it does something interesting?" No, that wouldn't do. I learned that I should have a hypothesis to test. "It would display traits of human cognition?" That was too broad (and bold) a claim to use as a hypothesis, according to my supervisor. At this moment I should have realized that this project was too big and undefined for an MSc thesis. But I was too determined to build it and I thought I could not possibly reduce it further. I would need this level of complexity to get it to do what I want. I still think I am right about that, but I have learned that there are more than one MSc theses hidden in this project and also that there is quite some complexity still missing for the agent to work the way I intended.

When my supervisor offered a user-centric hypothesis, i.e. that my system would deliver new and relevant content, I quickly accepted. I would have to assess its usability using a standardized test and compare it to other WWW content suggestion systems. That was the wrong turn. I had to design a proper user interface, had to conduct proper usability testing and my work would be compared with the giant systems of sites like Stumbleupon or Delicious. I didn't know whether I could possibly live up to that, but hey, I would build it and then I would see. And build it I did. I worked so much I almost cracked. I had to have an employee from the university's Student Life Center tell me to "be more German" about my work in order to make it through. Being more German, to him, meant to structure my day, fill it with breaks and regular food intake, rather than getting up and programming until I would drop into bed, interrupting work only by the quickest means of nutrition whenever I was too hungry to concentrate at all. It is kind of a "duh" advice, but I needed it and it worked. I did not get my work done as fast anymore, but at least I got it done at all. I was able to re-use a lot of the knowledge and literature I already had. All I had to add in terms of concepts was a Robert Plutchik's model of basic emotions, which I could readily implement. On the practical side of things, I learned quite a few things I had never done before. I learned how to code in JavaScript, how to create a Firefox browser extension, how to build a user interface with XUL, a new database system (HSQLDB) and how to access it from Java, how to do proper logging (with Log4j) and log based debugging. I also switched my Java IDE from Netbeans to Eclipse for this project, and I learned a lot about project management. All in two months of time. I then had another month for testing, analysis and writing up.

By the time I had finished programming, I couldn't bear to see the code anymore. I was done for, completely fed up with coding. I asked a lot of people to do some usability testing, and even though I received some early comments, most people did not bother testing it for a long enough period of time. In the end I had a single person fill out the usability questionnaire. It was a disaster. I spent so much time on making that damn graphical user interface pleasing to use and then almost nobody even tested it? Heck I even translated it to German and I did not have a single German speaking tester, my translated questionnaire counted zero participants! Truth be told, however, there were some bugs in the system which made it unpleasant and unproductive to use. But ready or not, I needed that usability testing for my dissertation! How would I assess the success now? Was it a failure? Yes, in a way it was a failure. It did do what it was supposed to, but it sucked at it, big time. Being a good researcher, I wrote up a long paragraph on limitations and future work in my dissertation. This was the best I could do at that point. While I don't have a lot to show for in terms of positive results, I have learned a lot. And more importantly, I did build it!

For more details on this project (including screenshots of the UI), take a look at my dissertation.

Living in England

Being a rather stereotypical German in this matter, I can't help but complain a bit about day to day life in England. Student accommodation sucks. You know it does when you freeze at night under your blanket unless you put on a jumper, your living room smells like a basement, when you notice the outer walls are made of cardboard, and when some eventful day the toilet flushes straight through the ceiling of your kitchen onto your stove... and despite all of that you are being told this were actually quite decent accommodation. Then, what's with them two taps at the sink, one too hot and the other too cold, that's plain ridiculous. I lost 10kg because I could not buy fastfood when seeing the inevitable result of eating it, shopping right next to me (I had never before seen so many obese people). Free health care is great, being told to take pain killers rather than seeing a specialist is not. British beer and British bread I could never get used to and don't get me started on British weather... If you're a German student thinking about going to England you may be in for a rough ride.

Now that I am done ranting, I have to say that I did like the city I lived in (Brighton). It was very liberal, very multi-cultural. It just had a good vibe about it. It seemed that people lived in a common way regardless of their cultural heritage. I did not experience any racism or major integration issues, which was nice to see. Maybe I did not look close enough, but here in Germany and also in Austria such issues are more visible.

The way people interact with one another is nicer in England, too. You bump into someone, you say you're sorry, whether you were the bumper or the bumpee doesn't matter. You ask how somebody is doing, whether or not you know them and you thank your bus driver for the transport. Even though it is most likely automated behavior for most British people, I enjoyed it a lot. It just seemed nice and it's not easy to get back to the "rude" German way of (not) interacting with strangers.

Resume and outlook

Totally worth it. If you get the chance to study at a good British university, you'd be stupid not to take it. It was way more competitive than what I was used to and I almost cracked under the pressure, but the education was great, the library had subscriptions to a ton of major journals and it felt like I was part of the scientific community.

What's next? I don't know. I went to England hoping I would find out what I would want to do next, maybe specialize somewhere and do a PhD. However, during the MSc all questions I had regarding living systems and biologically inspired computing have been answered satisfactorily. What is left are the great classic questions "What is the Universe?" and "What is consciousness?". I doubt I'd get into particle physics and, personally, I doubt physics will find an answer any time soon. Even though one of my favorite professors would most likely call me a "madman" now, joining the ranks of Konrad Zuse, Edward Fredkin and Stephen Wolfram, I can conceive of the universe being an algorithmic process taking place in a discrete network that just seems nice and continuous above Planck length. Plainly speaking, the world may be a giant computer. But it's difficult to stay scientific when discussing such matters. These debates quickly degrade into philosophical conjecture.

As for consciousness as a field of study, things are looking brighter and I might want to join the fun and try to make consciousness more tangible, more accessible to itself. Maybe do some brain-computer interfacing? Some neurofeedback? That's good stuff, but I need to learn more before I can make a decision to begin a PhD. I'm currently reading a book about consciousness and I hope that helps.

I don't really know how to proceed from where I stand. At the minute I am unemployed and about to receive welfare until I get assigned some job that will convert my time and energy into money. Really what I would need is unconditional basic income. If I could just sustain a rather comfortable life without worrying about the future, I know I could be creative and motivated. However, with the pressure of having to cover my living expenses, my options are limited and my creativity is gagged by fear. Where is my Star Trek utopia when I need it?

"The economics of the future are somewhat different. You see, money doesn't exist in the 24th century. The acquisition of wealth is no longer the driving force in our lives. We work to better ourselves and the rest of humanity." (Captain Jean-Luc Picard in the movie First Contact)